Essay in “Modern Loss” on my father Bo.

https://modernloss.com/what-it-feels-like-to-be-older-than-my-father/

When I was 17, my father Bo died unexpectedly. In an instant, gone was the rock of our family. I was still in high school, but part of me had to grow up immediately. From then on, I knew that life was fragile, that it could end without warning.

During those early years, I could barely speak about my father, the fear of falling apart protecting my fragile heart. I was young and old at the same time.

My father grew up in northern Sweden and brought us around the world as a diplomat for the United Nations. Bo loved learning and was kind and charismatic. He taught me history and physics, how to change a tire and to dance the waltz. At the mountain top, he shared nuts and chocolate from his backpack before leading us down ski trails through the woods, and he trained me in squash until I became my high school champion. Always up early, he brought tea to my room to wake me up so I’d make it to school on time. I can still envision him on a narrow bridge in rural Nigeria, negotiating with two opposing tribal chiefs who refused to back down, blocking traffic for miles. After an hour of my father’s patient diplomatic persistence, he managed to get the chiefs to overcome generations of strife and we continued on our journey.

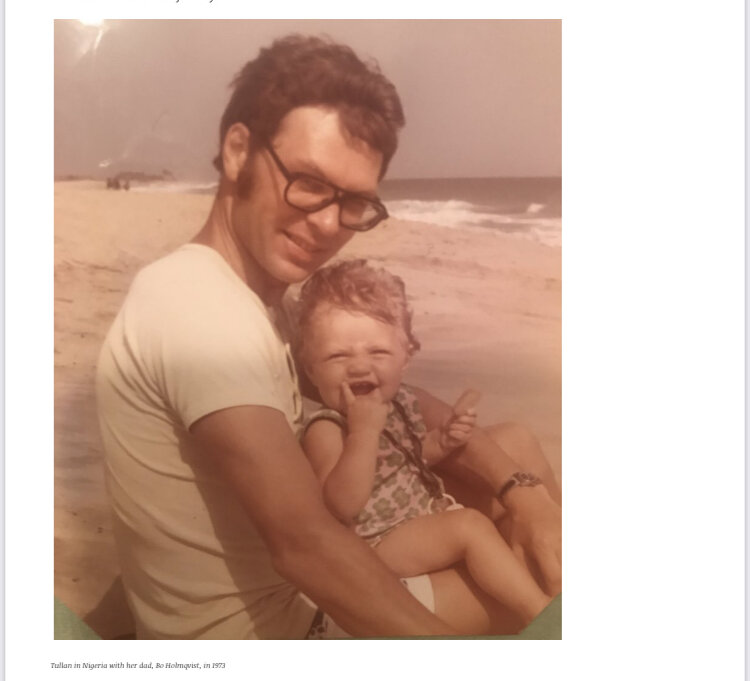

Tullan in Nigeria with her dad, Bo Holmqvist, in 1973

After he died, reminders of my dad have continually had me in tears or angry with life, both unpredictably and uncontrollably. During one mad Monday-morning rush, I thought I saw him at the train station in Stockholm, or when I saw a happy father-daughter duo eating lunch in a Chinatown restaurant or that empty seat at my October wedding in Florence. I have never stopped crying for all that he missed and all that I have lived without him.

As I approached 47, the age at which my father died, I worried about whether the pain would ever go away. Would I keep his memory at bay forever? But one day, I looked at my son Max, 11 at the time, enthusiastically telling me about the Bermuda Triangle with bright eyes, and I suddenly heard my dad. I remembered the book he had given me on unresolved mysteries, which fed my fascination for solving puzzles and ultimately inspired me to work as an investigator. I looked at my younger son Leo’s sturdy build and mischievous sense of fun, and there too I saw my father and remembered the jokes we shared.

I realized that Bo lives within them without them knowing. Or perhaps they do, since I’ve spoken to them so much about him? And I like to think he also lives in me and with me. Maybe it is time for me to live my life fully, as he had, even though he can’t be here.

Today, I’m older than my father was when he died. I still cry that my boys never got to meet him (do I call him grandpa even though he never really was a grandpa?) But now, when I’m ascending a mountain on the skilift, I know he is there with me, in that hidden daredevil both inside me and my little son Leo, ready to fly down the slopes together. In my need to solve conflicts and find common ground within the family, I am my father’s daughter, the peacemaker on the bridge in Nigeria. And when my darker moods settle, feeling the burdens of the world that need fixing, I recognize him there, too.

I would love to be able to pick up the phone and ask for his advice, but instead I listen to the quiet voice within me, the woman who has grown from the child who lost her dad too young. I feel gratitude for the unexpected beauty born out of the unpredictable pain. I have a new perspective on what really matters in this life and the love that continues through time and space.

Read this piece in Swedish here.

Tullan Holmqvist is a writer, investigator and actor, author of thriller The Woman in the Park, screenplays, stories and in upcoming films Before El Finā and Chiaroscuri.